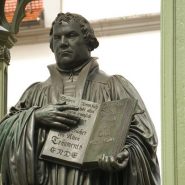

Professor Thomas A. Fudge on: Martin Luther, Father of the Reformation

Martin Luther’s 500 Year Old Wax Nose

Five hundred years ago, an Augustinian monk posted an announcement on a public bulletin board in a German university town. Hardly anyone knew him then. This rather ordinary event is still remembered. At the turn of the millennium, a group of reporters published a book listing 1,000 of the most important and influential people of the past millennium. Martin Luther (that obscure “drunken German monk” as Pope Leo X called him) was ranked third behind Johannes Gutenberg and Christopher Columbus. In 1934, a five-year old African-American boy named Michael King had his name changed to Martin Luther King, Jr. Others claim he inspired Hitler. Eighty million Christians today identify themselves as Lutheran. Luther once quipped that scripture seemed to have a wax nose which could be twisted into different shapes. A half millennium has shown that Luther’s nose is made of wax too.

The German edition of Luther’s works (WA) number 121 volumes in quarto format spanning about 80,000 pages. Luther expert Heiko Oberman kept the WA in his bedroom and claimed to have read all of Luther’s works. Almost everything conceivable has been written about Luther: relationship with his mother, the psychoanalytical “Young Man Luther,” his preoccupation with the Devil, allegations that images of him were fireproof, his earthy role as God’s Court Jester, his ghost, “Luther on Women,” his theology, ethics, sermons, thoughts about Jews, mystics, politics, ideas about reform, even right down to the comments he made in private conversation concerning banal topics such as women’s breasts and bowel movements. I have about 300 volumes in my personal library by or about Luther. Sometimes called the first modern man, Luther has been described by Erasmus as “a mighty trumpet of gospel truth” and by Emperor Charles V as a “demon wearing the habit of a monk.” Love him or loathe him, Luther is a major player in the history of western civilization. The advent of print culture ensured that Luther could not be ignored. And for the past 500 years he has not been ignored. Instead, he has been used, misused, abused, and even confused. His nose has proven to be ever so adaptable.

During the Reformation Jubilee and the 500th anniversary of Luther’s public emergence as a reformer, and with all of the attention being devoted to Luther, we should be cautious in privileging the Reformation as the pinnacle of medieval religious progress and the summit towards which religious thought and practice in the Middle Ages pointed, or the standard by which to evaluate other reform ideals. In other words, it is perilous to regard Luther as a high-powered drill exerting enormous change on the religious landscape of Europe at the end of the Middle Ages (to the virtual exclusion of everything else) while trying to make everything fit that assumption. Quite simply, Luther was not the sum and substance of the Reformation. There were many movements of reform. Luther may have been the father but he had many sons and daughters along with numerous bastard offspring that he was loathe to recognize.

For Luther and many others, Reformation was first and foremost a theological, not a personal, event. That fact has often, especially in our times, been overlooked. Luther famously wrote: “The first thing I ask is that people should not use my name, should not call themselves Lutherans. What is Luther? The teaching is not mine. I was not crucified for anyone. How did I, poor stinking bag of maggots that I am, come to where people call the children of Christ by my evil name?” One can only ponder how Luther might contemplate the 80,000,000 Christians who use his name. Luther denied any significant role in the reform of late medieval Christianity. “I did nothing. While I slept, or drank beer with my friends, the Word weakened the papacy more than any prince or emperor. I did nothing. The Word did it all.” Whatever happened and however it came about and despite his protests, Luther was deeply involved in a momentous paradigm shift. Reformation was historically decisive. How else do we explain its currency after 500 years? How else might we explain that, apart from a first-century Jewish rabbi named Jesus, more books have been written about Luther than anyone else in history?

Luther’s theological ideas (justification by faith, the priesthood of all believers, the joyous exchange, the real presence in the Eucharist) have mainly fallen into oblivion and Luther’s sixteenth-century concerns have become subordinated to twenty-first century preoccupations. There are good reasons to resist the opinion that Luther’s concerns are no longer relevant and in consequence there is some tendency to conjure contemporary relevance and applicability. Hence, we find studies of Luther posing the question “what Luther should say” or even more emphatically “what Luther has to say.” (i.e. Heiner Geißler, Was müsste Luther heute sagen? Berlin: Ullstein Buchverlage, 2015). The problem with this approach is underscored by the fact that a text without a context is a pretext for a proof-text. Luther’s wax nose is still malleable 500 years on.

Luther’s Reformation shattered the unity of western Christendom with widespread social and political ramifications that persist to the present. Perhaps unwittingly he opened Pandora’s Box and the Reformation spawned close to 35,000 organizationally distinct Christian denominations, a crisis of authority, rampant individualism, and a confused Christian identity. Luther wanted to revolutionize the church, and he developed a doctrine which had no moorings in the sacramental system of the medieval church. In effect, he precipitated a religious/theological Copernican Revolution which rocked the foundations of not only the Latin Church but western civilization prompting widespread chaos and controversy. In the end, Luther became fed up with the world and declared that he was like a “prime piece of shit” and the world a “big asshole,” each more than ready to be released from the other.

Once the voice of the western world, does he matter after 500 years? The ethos of heresy and dissent embodied by Luther that resisted the medieval church’s concerted efforts to maintain conformity on major points of theology and religious practice remains salutary. In different ways, Luther emphatically announced that “heretics have done nothing wrong against God” and one can call truth heresy if they like, but it is still truth. This remains an important principle. The problem is, postmodernity has helped to relativize and democratize truth. Luther would scorn the concept. But that is a result of the unintended consequences of replacing tradition with fragmented traditionalism. Luther’s wax nose applies. But so does the idea that Reformation is dynamic, not static. As the late George Wolfgang Forell put it thirty-five years ago, Reformation is not just something that occurred in a particular time and space. It should be something that becomes a permanent part of culture. It has to be taken seriously and be implemented by each generation. This relates to society, politics, and every other human institution. As for the Church, Luther can be recognized as a reformer only to the extent that Christian communities today are willing to be reformed.

After 500 years, Luther is still worth reading and it is only by engaging with his works that his ideas have contemporary meaning and the wax nose becomes less a caricature. His last words, scribbled on a scrap of paper, were “we are beggars, this is the truth.” In our arrogant, technologically-sophisticated age with its exploding font of information, we would all do well to keep that thought in mind.

Thomas A. Fudge

Thomas A. Fudge (PhD, Cambridge) is Professor of Medieval History at the University of New England.

His research and teaching interests focus on medieval and early modern European history. He is the author of fourteen books, the latest being Jerome of Prague and the Foundations of the Hussite Movement (OUP, 2016).